Chapter 2

Gomer and the Lost Sheep

Hosea 1:2 says,

2 When the Lord first spoke through Hosea, the Lord said to Hosea, “Go, take to yourself a wife of harlotry, and have children of harlotry; for the land commits flagrant harlotry, forsaking the Lord.”

The prophecy begins with an instruction from God for the prophet to marry “a wife of harlotry.” Hosea did so, knowing from the start that his marriage would not be a happy one. He understood from the beginning that he was to experience the same relationship with his wife that God had been experiencing with Israel. God had married Israel at Mount Sinai, and Moses officiated at the wedding. But Israel had continually committed spiritual adultery by going after other gods (husbands). Gomer would do the same, because she was a prophetic representative of Israel.

Hosea 1:3 continues,

3 So he went and took Gomer the daughter of Diblaim, and she conceived and bore him a son.

We have already noted that Gomer’s name was the official name of Israel, insofar as the Assyrians were concerned. The historians all agree that the name Gomri or Ghomri was derived from Omri, the Israelite king. Politically speaking, Omri was one of Israel’s greatest kings, though he was not a godly king. He established his own laws, rather than abiding by the divine law (Micah 6:16).

Omri became king of Israel in 1 Kings 16:23, reigning 12 years. His son was Ahab (1 Kings 16:29), who reigned another 22 years and is more well known for his marriage with Jezebel, the daughter of Ethbaal, the priest-king of the Sidonians (1 Kings 16:31).

Obviously, the Assyrians could not have called Israel by the name Ghomri prior to the reign of Omri himself. So this prophetic name (which means complete) foretold the end of Kingdom of Israel on account of the sins of the house of Omri and Ahab.

Two Gomers

There were two people called Gomer in Scripture. The first was a son of Japheth (Gen. 10:2) who, along with his brothers, Magog, Madai, Javal, Tubal, Meshech, and Tiras, are the subject of Ezekiel 38 and 39. The second Gomer, however, is not a man, but a woman, the wife of Hosea. Israel was not named for Japheth’s son, but for King Omri, who lived many centuries later.

In the past 150 years, prophecy teachers have confused the two Gomers, and this has caused untold confusion in church teaching. Scofield was hardly the first to confuse the two, but he certainly popularized the confusion more than anyone else during the early 20th century in his reference Bible. In his notes on Gen. 10:2 he comments on the name Gomer, son of Japheth, saying,

“Progenitor of the ancient Cimerians and Cimbri, from whom are descended the Celtic family.”

He was correct in identifying Gomer as the progenitor of the Celts. However, he confused the two Gomers. Actually, the progenitor of the Celts is Gomer, the wife of Hosea, or Ghomri, the House of Israel. Of King Omri, Scofield says nothing. Either he was ignorant of history or he ignored it.

Dr. Bullinger, author of The Companion Bible, also missed this historical detail. In his notes for Gen. 10:2, he writes:

“Gomer. In Assyrian Gimirri (the Kimmerians of Herodotus). Progenitor of the Celts.”

Bullinger reinforces this in his notes on Ezekiel 38:6, where Gomer is listed with his brother nations as invaders of the mountains of Israel. There he writes:

“Gomer. Also descended from Japheth (Gen. 10:3).”

This note is actually correct, because the Gomer in Ezekiel 38:6 is indeed the Gomer who is descended from Japheth in Gen. 10:3. However, the confusion comes when anyone looks up his notes on Gen. 10:2 and reads that this Gomer is the same as the “Assyrian Gimirri” (or Gomri), “progenitor of the Celts.” The reader is given the false assumption that the Celts were to invade the mountains of Israel.

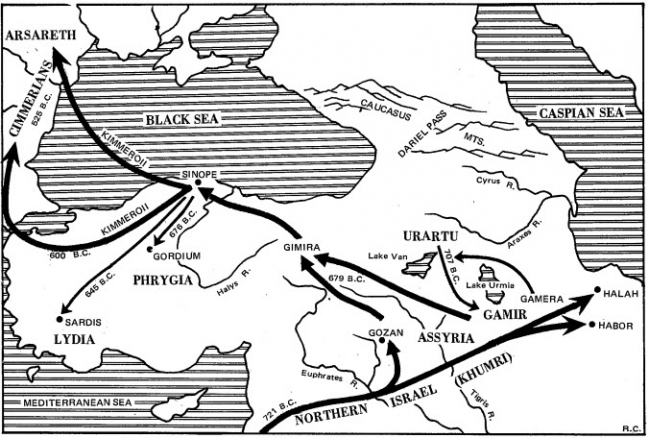

The Japhetic Gomer is an invader; Hosea’s Gomer is the one being invaded. Obviously, they are not the same Gomer. Yet this simple case of mistaken identity has brought untold confusion to the minds of prophecy teachers for more than a century. The Gimirri in the Assyrian records are indeed progenitors of Celts, but all of the archeological monuments show us that they are the Israelites who were taken to Assyria as captives.

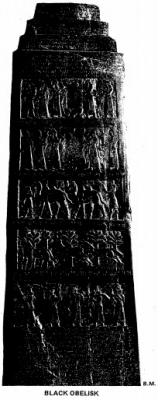

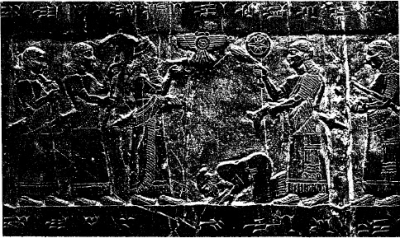

Not only the Moabite stone confirms this, but also the Black Obelisk of Shalmanezer. It portrays Jehu, “son of Omri,” [Bit-Khumri] giving tribute to the king of Assyria.

|

Figure 1 - Jehu bowing down to the king of Assyria Figure 1 - Jehu bowing down to the king of Assyria |

Other historical references to the Bit-Khumri or Bit-Humri can be found here:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Omrides

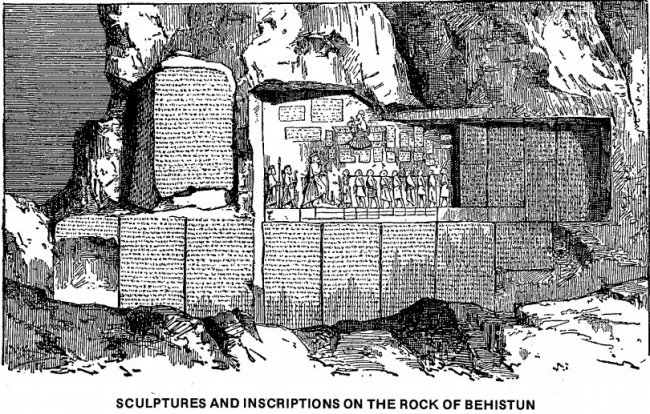

The Celtic Israelites were known in history by other names as well. When King Darius of Persia died, he was placed in a tomb in the mountain known as Behistun.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Full_translation_of_the_Behistun_Inscription

Inscribed in three languages were all of the nations and tribes that he ruled. The Gimirri are called Saka and Sakka in other languages. The Saka, of course, are the same as the Sacae (Kimerians) described by the Greek historians. The Roman historians, writing in Latin, wrote this as Saxons.

Most of Europe (other than along the coasts) was populated by Celts, Saxons, and other Israelites after the fall of Nineveh in 612 B.C. The lost House of Omri (i.e., Israel) was not really lost at all—except to Christian prophecy teachers, it seems. Historians know very well that the Israelites were the Gimirri and the Sakka, for they are very familiar with the Moabite Stone, the Black Obelisk of Shalmanezer, and the Behistun Rock. They also know that the Gimirri-Saka immigrated into Europe, many of them through the Caucasus Mountains, and for this reason they have labeled them Caucasian.

The Lost Sheep

Under any other circumstances, these facts would be well known to all. However, it was in the divine purpose to hide the Israelites, so that most of them would lose their sense of identity. This was part of the divine judgment upon Israel. They were to become “lost sheep” (Jer. 50:6). Ezekiel, too, says that they were to be “scattered” and “lost” (Ezekiel 34:4, 5, 16) and that “there was no one to search or seek for them” (Ezekiel 34:6).

There are many who search for “lost souls,” but few who search for “the lost sheep of the House of Israel,” as Jesus called them in Matt. 10:6. Those lost sheep were not Jews living in Judea at the time of Christ. Jesus sent His disciples north to the Gimirri, some of whom had been conquered by the Greek empire and were currently within reach of missionary trips (John 7:35). Peter wrote his first letter to the “aliens of the [Israelite] dispersion… who are chosen according to the foreknowledge of God the Father” (1 Peter 1:1, 2). Later, in 1 Peter 2:9 he again writes to them: “But you are a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a people for God’s own possession.”

In 1 Peter 2:10 the apostle identifies these people with two of the sons of Hosea and Gomer:

10 For you once were not a people [Lo-ammi], but now you are the people of God [Ammi]; you had not received mercy [Lo-ruhamah], but now you have received mercy [Ruhamah].

This is a direct quote from Hosea 2:23. It is only when we study Peter’s writings with the prophecies of Hosea that we can really understand what the apostle was saying. Peter was writing to some of the dispersed Israelites living in the northern part of Asia Minor (now Turkey) in the provinces of “Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, Asia, and Bithynia” (1 Peter 1:1). These areas were accessible to Jesus’ disciples.

http://www.bible-history.com/geography/maps/map_asia.html

It is my belief that when Jesus sent His disciples on a mission to the lost sheep of the House of Israel, they made many new friends and converts as they healed the sick, raised the dead, cleansed the lepers and cast out demons (Matt. 10:6-8). Many years later, Peter wrote his letters to them. Even James, the brother of Jesus, corresponded with them (James 1:1), although he had not been among the original twelve disciples, nor had he been among the seventy that were sent out in those early years.

The point is that these Israelites were not dispersed Jews. They were Israelites who had been dispersed more than 700 years earlier. The Jews in the first century certainly knew where many of these Israelites were located. In fact, the first-century Jewish historian, Josephus, gives us their location. He wrote:

“Wherefore there are but two tribes in Asia and Europe subject to the Romans; while the ten tribes are beyond Euphrates till now; and are an immense multitude, and not to be estimated by numbers.” [Antiquities of the Jews, XI, v, 2]

Josephus knew that the Jews (“two tribes”) were not the Israelites (“ten tribes”). More recently, The Jewish Encyclopedia has written:

“As a large number of prophecies relate to the return of ‘Israel’ to the Holy Land, believers in the literal inspiration of the Scriptures have always labored under a difficulty in regard to the continued existence of the tribes of Israel, with the exception of those of Judah and Levi (or Benjamin), which returned with Ezra and Nehemiah. If the Ten Tribes have disappeared, the literal fulfilment of the prophecies would be impossible; if they have not disappeared, obviously they must exist under a different name.”

http://jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/14506-tribes-lost-ten

While many Bible teachers say that the Jews are Israelites, the Jewish scholars themselves have always maintained that they are from the nation of Judah, which consisted of Judah, Benjamin, and Levi. They do not claim to be of the ten tribes of Israel. Their point is well made, then, that “If the Ten Tribes have not disappeared… obviously they must exist under a different name.” Jewish scholars have taught very consistently for thousands of years that the ten tribes did NOT return to the old land with Judah after the Babylonian captivity ended. This is proven by many biblical statements, such as 2 Kings 17:23, which is widely regarded to be an insertion by Ezra, who compiled the canon of the Old Testament. It reads,

23 until the Lord removed Israel from His sight, as He spoke through all His servants the prophets. So Israel was carried away into exile from their own land to Assyria until this day.

Until what day? Until Ezra’s day. This statement would have no meaning if it had been written shortly after the Assyrian invasion. Obviously, it was meant to tell us that even after the Babylonian captivity ended in 534 B.C., Israel had not returned to the old land. That Jewish nation was known as Judah in Hebrew, or as Judea in Greek.

If that is so, then the current Jewish state is NOT the “Israel” that is represented by the lost ten tribes (Gomer). Their use of the name Israel is only a political name, designed to deceive Christians into supporting it as “the restoration of Israel” according to Bible prophecy. But the Jewish immigrants to the state of Israel could never fulfill God’s promises of the restoration of the ten lost tribes. On the other hand, we know that God Himself dispersed the Israelites and caused them to become lost insofar as their identity was concerned.

If, as the scholars say, “they must exist under another name,” what is that name? It is specifically revealed in the book of Hosea as Gomer, which the Assyrians wrote as Gimirri, which the Persians wrote as Saka, the Greeks wrote as Sacae, and the Romans as Saxons.

Once we have properly identified the subject of Hosea’s prophecy, we are in a good position to understand this portion of Scripture. However, let no one think that these prophecies include only biological Israelites, for Isaiah 56:6-8 makes it very clear that in the regathering of Israel at the end of the age, many others will come with them to be part of God’s (new) Covenant people. The covenants of God come through Israel, but anyone may become an Israelite by nationality. The dividing wall has been broken, Paul says in Eph. 2:14, 15, making all people “one new man, thus establishing peace.”