Chapter 2

Forty Years of Grace

In Ezekiel 4:5, the prophet was told to lie on his left side for 390 days, a day for a year, to intercede for the House of Israel. Then in verse 6 he was told to lie on his right side for 40 days, a day for a year, to intercede for the House of Judah. Ezekiel’s actions established grace periods for Israel and Judah on very different time lines.

Our present focus is on the 40-year grace period that Ezekiel obtained for the House of Judah. Certainly, there could be more than one fulfillment of this prophetic time period, but the 40-year period leading to the fall of Jerusalem in 70 A.D. is relevant to us now.

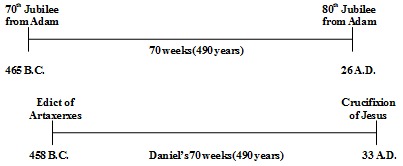

This 40-year period follows the 70th week of Daniel, which extended from 26-33 A.D. The 70 “weeks” (i.e., Sabbatical cycles of 7 years each) began with the Edict of Artaxerxes I of Persia in the Spring of 458 B.C. Because his Edict came 7 years after the 70th Jubilee from Adam (465 B.C.), the end of the 70 weeks was also 7 years past the 80th Jubilee (26 A.D.).

Daniel's seventieth week extended into the first rest-year cycle of the 81st Jubilee from Adam.

In the middle of Daniel's 70th week was September of 29 A.D., when Jesus was baptized by John to begin His ministry. John had begun to minister six months earlier when he turned 30 years of age, according to the law of priesthood (Num. 4:3). John was about six months older than Jesus, their mothers being pregnant at the same time (Luke 1). So when Jesus turned 30 in September of 29 A.D., He came to John for baptism.

A few months after this, John was cast into prison for preaching against Herod's unlawful marriage to his brother's wife (Matt. 14:4). We know that even after Jesus had been baptized, He recognized that He still had to wait for John to complete his ministry, and for this reason, at the marriage feast of Cana, Jesus told them “My hour has not yet come” (John 2:4). It is obvious that Jesus was restrained in His ministry until John was taken out of the way. But Mark 1:14, 15 tells us,

14 And after John had been taken into custody, Jesus came into Galilee, preaching the gospel of God, 15 and saying, “The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God is at hand; repent and believe in the gospel.”

The high priests in those days were appointed by the political authorities and were no longer chosen according to the law of Moses. So while they were legitimate in the eyes of men, they were not necessarily so in the eyes of God. In my view, God recognized John the Baptist as the high priest of the day, for his father Zacharias was a priest (Luke 1:5).

Jesus was destined to become the high priest of a new Order, but He could not fully enter this calling until John's time of ministry had been completed. And so, when John was cast into prison, Jesus came into Galilee to preach the gospel, picking it up where John had left off. Even so, John's imprisonment was a transition into the new dynasty of priesthood (Melchizedek Order).

When John died, then was Jesus fully invested with the high priesthood in the sight of God. John died childless, and so the high priesthood (in the eyes of God) passed to his nearest relative, his first cousin, Jesus Christ. This also explains why Jesus was reluctant to begin His ministry until John was cast into prison and executed (John 2:4).

John was executed at a Passover. We know this because after his beheading, his disciples came and told Jesus (Matt. 14:12). Jesus immediately took a boat to the other side of the Sea of Galilee. The people followed Him, and there He fed the 5,000, as Matthew 14 tells us. In John's Gospel, we learn that Jesus fed the 5,000 shortly after the Passover (John 6:4), and that he fed them with “barley” (John 6:9). This signifies the day of the first fruits offering of barley on the day after the Sabbath after Passover (Lev. 23:11). Jesus fed the 5,000 with newly-harvested barley to connect the event with His resurrection on that day three years later.

So John was executed at Passover of 30 A.D. about six months after he had baptized Jesus. John was about 31 years old, while his cousin, Jesus, was about 30½. Jesus then was crucified three years later on Passover of 33 A.D. precisely at the end of Daniel's 70 weeks.

The nation's 490-year grace period had ended, where God had forgiven the nation once a year on the Day of Atonement a full 490 times, as mandated in Matt. 18:21, 22. Only in 33 A.D. did God's obligation to forgive run out, and then He brought the nation (and the world) into accountability at the cross, paying the penalty Himself (Matt. 18:23). If God had brought them into accountability earlier, He would have violated His own prophetic principle of judgment.

For a more complete discussion of Daniel's 70 weeks, see the latter part of chapter 9 of my book, Secrets of Time.

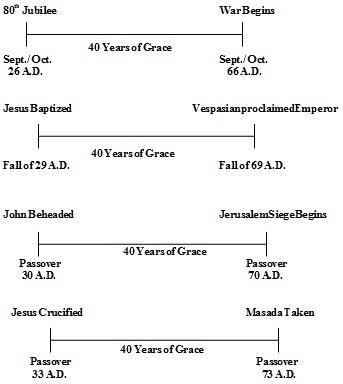

So there are at least four important dates that begin the 40-year grace period for Judah:

1. September of 26 A.D., which was the 80th Jubilee and the beginning of Daniel's 70th week.

2. September of 29 A.D., which was the time of Jesus’ baptism on the Day of Atonement.

3. Passover of 30 A.D., which was the time of John’s execution.

4. Passover of 33 A.D., which was the time of Jesus’ crucifixion.

These beginning points all manifest important end points 40 years later. The first cycle ends in September of 66 A.D. Though Josephus tells us that the beginning of the great revolt began at Passover of 66, the actual outbreak of violence, in terms of war, occurred at the time of the feast of Tabernacles (Sept/Oct). This was when the Judeans actually destroyed Rome's 12th Legion under Cestius Gallus, the Governor of Syria. This is recorded by Josephus in Wars of the Jews, II, xix.

During that first conflict in 66 A.D., the Roman army at first had nearly taken the city of Jerusalem, but some communication problem made them withdraw before claiming victory. It was during their retreat that the Legion was destroyed.

It may be that God caused the Roman Legion to withdraw in order to allow the Christians in Jerusalem to leave the city before Jesus' prophecies about its destruction were fulfilled. All we know is what Eusebius tells us in Ecclesiastical History, III, 5,

“Further, the members of the Jerusalem church, by means of an oracle given by revelation to acceptable persons there, were ordered to leave the City before the war began and settle in a town in Perea called Pella. To Pella, those who believed in Christ migrated from Jerusalem; and as if holy men had utterly abandoned the royal metropolis of the Jews and the entire Jewish land, the judgment of God at last overtook them for their abominable crimes against Christ and His apostles, completely blotting out that wicked generation from among men.”

Eusebius did not define what he meant by “before the war began.” Was this before the 12th Legion was destroyed? Or was it the inevitable war that came in 67 A.D. when Rome brought retribution to avenge the 12th Legion? Whatever the case, the Jerusalem church remembered Jesus' words, and apparently also received prophetic utterances, which told them not only to leave but also where to go. They went to Perea, which was beyond the Jordan River. In other words, they left Judea altogether.

Looking ahead to today, I believe that a similar evacuation will take place among the Christians in the present-day Israeli state who take heed to the prophetic word today. Those who do not do so will probably suffer the fate of the rest of the population when Jerusalem is destroyed again for the final time. When that day arrives, then will the prophecy of Jeremiah 19:11 be fulfilled, and Jerusalem will be destroyed in such a way that it will never again be rebuilt.

As we can see by the charts on the next page, there are 40-year connections with four beginning points and four ending points in the grace period for Judah in the first century. The beginning points were September or October of 26 and 29 A.D., and Passover of 30 and 33. Essentially, the 70th week of Daniel encompasses all four of the beginning points above.

Adding 40 years to each of these beginning points brings us to September or October of 66 and 69, and Passover of 70 and 73.

The Revolt broke out in September or October of 66, when the Judeans destroyed Rome's 12th Legion while the people were on their way to Jerusalem to observe the Feast of Tabernacles.

This brought retribution, and Rome sent Vespasian and his son, Titus, to quell the revolt. They took control of most of the country by the summer of 68, but then Nero committed suicide on June 9, 68 A.D. Nero's death put the war in Judea on hold, while Vespasian waited for new instructions from the next emperor.

But the Spanish provinces also had revolted under the leadership of Galba. Nero had many enemies by setting fire to Rome in July of 64, and much of the city yet remained in ashes. Suetonius writes about Nero's suicide after the Senate had condemned him to death:

“While he [Nero] hesitated, a letter was brought to Phaon by one of his couriers. Nero snatching it from his hand, read that he had been pronounced a public enemy by the Senate, and that they were seeking him to punish him in the ancient fashion, and he asked what manner of punishment that was. When he learned that the criminal was stripped, fastened by the neck in a fork and then beaten to death with rods, in mortal terror he seized two daggers.

“And now the horsemen were at hand who had orders to take him off alive. When he heard them, he quavered, 'Hark, now strikes on my ear the trampling of swift-footed coursers.' [a quote from Homer's The Iliad, 10.535], and drove a dagger into his throat, aided by Epaphroditus, his private secretary.” [Seutonius, Lives of the Caesars: Nero, XLIX]

The next emperor, Galba, had been governor of Spain and had been induced by Vindex, Governor of Aquitania, to lead the revolt against Nero. When Vindex suddenly died, he was frightened, but then got word of Nero's death as well. The people and Senate swore allegiance to Galba, and so he became the next Caesar for a few months.

So ended the last of the Julian dynasty of emperors that had begun with Julius Caesar a century earlier. Nero's death marked the beginning of the reign of military generals. But Galba's avarice and cruelty turned the people (and especially the soldiers) against him almost immediately. He reigned only seven months before Otho killed him in January of 69.

Otho ruled for a short time, and then was overthrown by Vitellius. But Vitellius’ reign was short-lived as well. Suetonius tells us:

“In the eighth month of his reign [Vitellius] the armies of the Moesian provinces and Pannonia revolted from him, and also the provinces beyond the seas, those of Judea and Syria, the former swearing allegiance to Vespasian in his absence and the latter in his presence.” (Lives of the Caesars: Vitellius, XV]

Vitellius was put in prison, brought to the Forum. There he was tortured for a long time and finally killed and dragged off with a hook and his body thrown into the Tiber River.

Vespasian was more successful. He began his ”ministry” as Roman Emperor in the fall of 69 A.D., precisely 40 years after Jesus had been baptized to begin His ministry in September, 29 A.D. Prophetically speaking, Vespasian was the general of God's army, sent to “set their city on fire,” as Jesus foretold in Matthew 22:7,

7 But the king [i.e., God] was enraged and sent His armies and destroyed those murderers, and set their city on fire.

This was the same Vespasian who had fought in Britain earlier, as Suetonius tells us:

“In the reign of Claudius he was sent in command of a legion to Germania, through the influence of Narcissus; from there he was transferred to Britannia, where he fought thirty battles with the enemy. He reduced to subjection two powerful nations, more than twenty towns, and the island of Vectis [The Isle of Wight], near Britannia, partly under the leadership of Aulus Plautius, the consular governor, and partly under that of Claudius himself.” [Lives of the Caesars: Vespasian, IV]

You may recall from Book I the name of Aulus Plautius, who was the general that captured the British royal family in 52 A.D. At that time, Emperor Claudius himself had come to Britain with some elephants which stampeded the horses of the British chariots.

When the troops proclaimed Vespasian as Roman Emperor in 69 A.D., he was leading Rome’s army in Judea. By this time the countryside had been subdued, and he had taken Josephus captive at the battle of Jotapata. Suetonius tells us:

“When he consulted the oracle of the god of Carmel in Judea, the lots were highly encouraging, promising that whatever he planned or wished, however great it might be, would come to pass; and one of his highborn prisoners, Josephus by name, as he was being put in chains, declared most confidently that he would soon be released by the same man, who would then, however, be emperor.”

Vespasian was proclaimed emperor by the troops in July of 69, and the prefect of Egypt was the first to take an oath of loyalty to him. Vespasian then left his son, Titus, as head of the army in Judea and went to Alexandria to secure the strategic support of Egypt. It was while he was in Egypt that letters arrived, telling him the news that Vitellius had been deposed and killed. He then took a ship to Rome in December.

When he had secured his place as Emperor in Rome, he sent instructions to his son, Titus, to begin the siege of Jerusalem. The siege then began on Passover morning of 70 A.D. This was precisely 40 years after the beheading of John the Baptist. This is confirmed by Josephus in Wars of the Jews, V, xiii, 8, when he tells us that the casualties of that war were:

“. . . no fewer than a hundred and fifteen thousand eight hundred and eighty dead bodies, in the interval between the fourteenth day of the month Xanthicus, or Nisan [the month in which Passover was celebrated], when the Romans pitched their camp by the city, and the first day of the month Panemus, or Tamuz” [when the city was destroyed].

In other words, the siege began on the fourteenth day of Nisan, which was the day that the people were supposed to kill the Passover lambs. It was precisely 40 years from the death of John (30-70 A.D.).

After the fall of Jerusalem, the only stronghold to be subdued was Masada, a fortress on top of a mountain with only one narrow, steep path up the top. The Sicarii (assassins) had taken this fortress in 66 A.D. just before the beginning of the war.

In order to take this fortress, the Romans used Jewish labor to build a ramp of earth and rocks, which took considerable time to complete. They finished it on the 14th day of Nisan in 73 A.D. and decided to take the fortress the next day. But that same night, the defenders of Masada committed suicide rather than allow themselves to be taken captive. The only ones who escaped were two women and five children who were able to hide. Josephus tells us in Wars of the Jews, VII, ix, 1,

“This calamitous slaughter was made on the fifteenth day of the month Xanthicus, or Nisan.”

This was the Day of Passover, the first day of Unleavened Bread. The suicide occurred on the anniversary of that first Passover night when the first-born of Egypt were slain in the days of Moses. But this time it was the Jewish Sicarii who were killed, identifying them with those who were not covered by the blood of the lamb.

This occurred precisely 40 years after Jesus' crucifixion as the Lamb of God. The Sicarii of Masada were unbelievers, much like the Egyptians in Moses' day who had refused to apply the blood of the lamb to their homes on that first Passover evening.

This ended the Revolt as well as the 40 years of Grace which Ezekiel had established for them through the discomfort of intercession. The people did not repent of their rejection of John or of Jesus. Instead, their hearts were hardened, and so God sent His armies to destroy their city as Jesus had prophesied.